Sargassum is a genus of brown algae found in the tropical and subtropical Atlantic. Two species (Sargassum natans and Sargassum fluitans) have become holopelagic, reproducing vegetatively and never attaching to the seafloor during their life cycles. This website deals with these free-floating species, which have been named the Algae of the Year 2024 by the German Botanical Society. Sargassum obtains its buoyancy from its gas-filled bladders and has long, strap-like, and leafy fronds that are usually golden-brown to dark brown in color. Sargassum serves as a critical habitat and nursery for many species and it provides food, shade, shelter and breeding ground when it floats in the open ocean. Large floating masses of Sargassum can drift with ocean currents and cover vast areas, forming what is known as the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic Ocean. Since 2011, however, Sargassum also occurs in large quantities in the Caribbean, including: Barbados, Martinique, the Dominican Republic, Guadeloupe, and Mexico. While Sargassum plays an essential ecological role in marine ecosystems, excessive blooms or influxes can become a problem for coastal regions. These unusually large and persistent Sargassum blooms have led to concerns about their impact on tourism, coastal ecosystems, and local economies. Research and monitoring efforts are ongoing to better understand Sargassum blooms, their causes, and potential solutions for managing their environmental and economic effects. Fieldwork in these regions demonstrate that people by no means interpret Sargassum in the same fashion; instead, multiple perspectives, practices of dealing with it, and future imaginaries have emerged, highlighting that the arrival of Sargassum is, indeed, ambivalent.

The Great Mayan Reef, officially known as the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, stretches 1,000 kilometers along the Caribbean coasts of Mexico, Belize, and Honduras. It is a key component of the Caribbean ecosystem. The reef system is degrading at an alarming rate, and one suspected actor is Sargassum, which makes photosynthesis below the surface more difficult for underwater flora and fauna. Sargassum has also been associated with degraded water quality, depleting nutrient levels and changing the colors of coastal waters. A damaged reef is a significant environmental problem, and goes hand in hand with a damaged beach, as reef degradation leads to beach erosion.

The Mexican Caribbean is home to many sea turtles – but not a home without struggle. Sea turtles were hunted for both food and trophy for centuries. In addition, pollution, industrial fishing practices, sea-based tourism and coastal development are impacting sea turtle populations significantly. In Akumal Bay, whose name means ‘place of the turtles’ in the Mayan language, efforts are in place to protect loggerhead and green turtles. Beached Sargassum poses a challenge for local species. Turtles can get trapped in the tangled mats of seaweed, preventing them from laying eggs, or if they do manage to nest, the rotting Sargassum on the beach poses a toxic threat to the eggs and eventual hatchlings. It makes their ‘march into the sea’ all the more daunting, as they must overcome Sargassum barriers to make it into the water.

Seagrass meadows (underwater fields of grass) are an unsuspecting – yet critical – actor in ensuring beach paradise along the Caribbean coastline. They play a pivotal role in coastal ecosystems, contribute to coastal stability, prevent coastal erosion, slow down storms and hurricanes, feed various species, and offer a habitat to many different creatures. Yet the condition of seagrasses in Mexico and elsewhere is deteriorating increasingly. Seagrass beds are suffering from climate change and anthropogenic impact on the environment. One culprit in seagrass deterioration is Sargassum. Its arrival changes the pH level, temperature, and quality of coastal waters as well as preventing photosynthesis of seagrass by blocking out sunlight under the surface. Deteriorating and dying seagrass meadows create vulnerability in the coastal ecosystem and threaten various species and industries reliant on it.

“Since we have had Sargassum arrivals, I realize more and more dead seagrass on the beaches. I have learned that when there is Sargassum the seagrasses die, because of the turbidity and the low oxygen Sargassum brings about. That really worries me because we need seagrasses as coastal protection.”

– Flora, marine biologist

“Where the Sargassum brown tide is, everything dies. Everything on the bottom. All the benthic species, any small corals, all seagrasses, and all fish. Everyone who could not move out in time dies, because everybody needs oxygen.”

– Eva, marine biologist

“The beaches are eroding because the seagrass is disappearing. Because the seagrasses, they keep the sand on the ridge.”

– Eva, marine biologist

The Great Mayan Reef is home to some of the most impressive fish species. Their bright colors and mesmerizing biodiversity attract tourists from all over the world. But the arrival of Sargassum in the region is changing the habits of Caribbean fish. Around the reef and in coastal waters, Sargassum deprives waters of oxygen and change its pH, temperature, and quality. The algae transform the reef – once a haven for fish – into an inhospitable environment, pushing fish like parrot fish, angel fish, eels, and surgeons to move closer to shore, and ultimately resulting in unprecedented fish mortality. In the open ocean, the interaction between Sargassum and fish is different, as the algae acts like a refuge, providing food, shelter, and protection in open waters. Whether along the coast or in the open ocean, Sargassum is changing the way fish live in the Caribbean.

Fishing secures as the livelihood of many people and families in the Caribbean. It is, however, vulnerable to the ever-fluctuating environment. The repercussions of climate change have shifted the way fisher fish in the Caribbean. Thick mats of Sargassum prove to be a new obstacle to navigate through and around for fisherman – sometimes entangling boats and damaging engines. Massive fish mortality has lessened available fish stocks. New species of fish have arrived – such as the Amber fish – that have changed the type of fish being caught. Some have also resigned and given up fishing altogether, looking for other jobs instead.

Tour guides along the Riviera Maya offer snorkeling trips, fishing adventures, and turtle encounters. They walk up and down the beaches, wait in front of jetties for newly arrived guests, or roam the streets to attract potential customers. Tour guides are worried about and already affected by tour cancellations, less demand, and the Sargassum’s impact on marine life. In addition, they must invest time and financial resources in cleaning and removal activities. What challenges them is the fact that Sargassum blooms are hard to predict and are subject to seasonal variability, making planning their activities more difficult. To mitigate the impact the algae has on their businesses, tour guides and operators have begun diversifying their offerings, adjusting schedules, and educating tourists about the conditions on the beach and possible alternatives to spend their holidays.

“I have many pictures on my phone with very bad Sargassum conditions. When clients approach me, I show them how bad it can get – and assure them, that they won’t have to encounter that if they book with me!”

– Alejandro, tour guide

“In the past, travelers only inquired about the security situation in the Yucatán when they contacted me about my tours. But now it is always the question about Sargassum. Sargassum first, security second. The algae arrival has really changed their concerns.” Nina, tour guide

– Nina, tour guide

“I have studied marine biology, and I loved what I was doing. But together with my family, I decided not to work in the field, but instead join the tourism industry. That pays much better! And for many years it did, but now I can feel the difference. I sell my snorkeling tours less often, and tourists tend to spend more time at the pool instead of on tours.”

– Ramón, snorkel guide

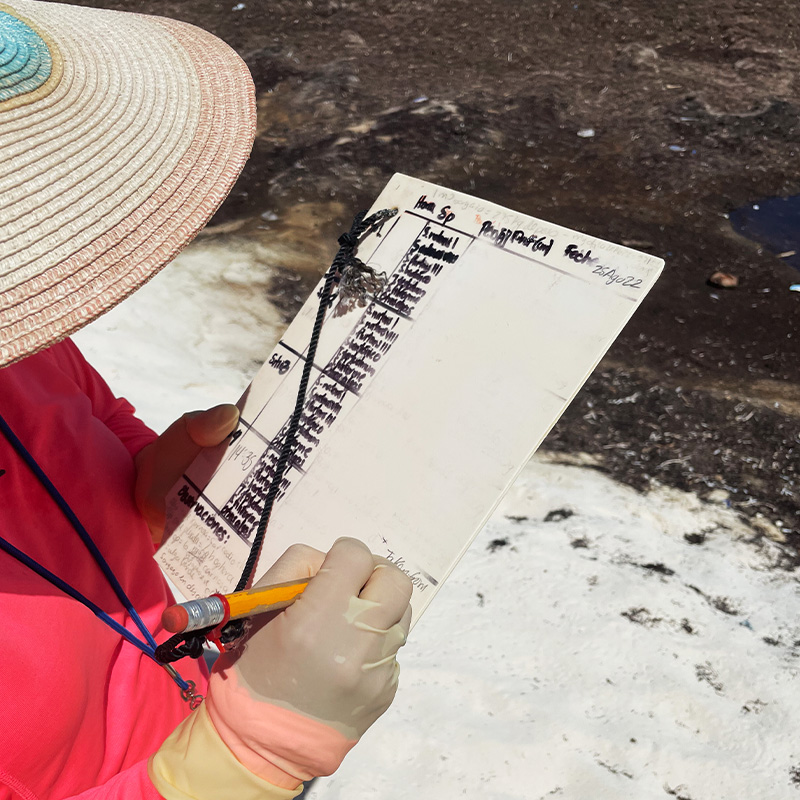

Home of the Great Mayan Reef, the Caribbean is no stranger to scientists who are often the go-to people for information and knowledge about happenings in the ocean, reef, and coastal ecosystems. With excessive Sargassum influxes, the public and the media have turned to researchers for answers. Sargassum necessarily shifted research interests, projects, and programs to try to gather as much information as possible on what was causing Sargassum influxes, what the ecosystem impacts were and what avenues of action existed to move forward. Ongoing research continues to expand and deepen the understanding of Sargassum and its entanglement in the larger coastal, reef, and ocean ecosystem, even if it has the challenge of keeping up with pace of environmental change due to Sargassum.

“I never thought I need to work on coastal restoration one day, but that is all I am now working on. How to restore the seagrass meadows of the Mexican Caribbean is now one of my major concerns. I’m not studying flowers anymore, the bugs pollinating the flowers, etc. I’m studying how to restore the shore. Sargassum changed my work and research interest tremendously.”

– Flora, marine biologist

“The knowledge we have about Sargassum is relatively brief because it has just been a phenomenon here for a few years. Many things about the algae remain unclear, and the more research we do, the more questions we have. To be honest, we have very little information as of now”.

– Tadeo, marine biologist

“It was not me who chose Sargassum, it really chose me. I had never intended to research these algae, but now that it is populating our coast, I must.”

– Loreena, marine biologist

The arrival of atypical amounts of Sargassum and the urgency to rid the waters and the beaches of its presence has made beach cleaners all the more important in the Caribbean. Cleaning the beach can be done in a variety of ways. Some cleaning crews use heavy machinery to scoop and transport the Sargassum away from the coast. Another method is the use of a giant sieve that filters sand from seaweed in effort to avoid beach erosion and sand loss through the cleaning process. Often, Sargassum is cleaned away manually by laborers with rakes in hand. It’s challenging and often precarious work that is not without physical risk. Rotting Sargassum releases ammonia and hydrogen sulfite, which at prolonged exposures can make humans sick and cause respiratory distress. During peak times, the challenging and dangerous work of cleaning the beach must be repeated every morning with the new arrival of Sargassum.

Get rich of it or get rid of it – is a sentiment prevalent in the field. While many people are hoping for a future without Sargassum, others believe that it holds great potential for economic success. Different entrepreneurs are working towards products based on Sargassum: they include fertilizer, biofuel, vegan leather, soap, paper, and bricks to build houses. Of course, cleaning beaches and removing Sargassum also has become an industry itself in the Caribbean. The Sargassum entrepreneurship scene is a growing one, that rapidly internationalizes and connects – often young – minds from across the world.

The white, flawless sand of the Mexican Caribbean is an integral part of the image of beach paradise that underpins the region’s tourism industry. But this image is becoming more and more of a challenge to make good on. Sand is disappearing due to coastal erosion brought about by excessive arrivals of Sargassum which have prompted intense and frequent cleanings where sand, entangled with the rotting seaweed, is often transported away from the beach and buried further inland. The sand that is left of the beach is also changing, from the soft and white expectation to a hard and greyish brown reality, resulting from Sargassum decomposition on the beach.

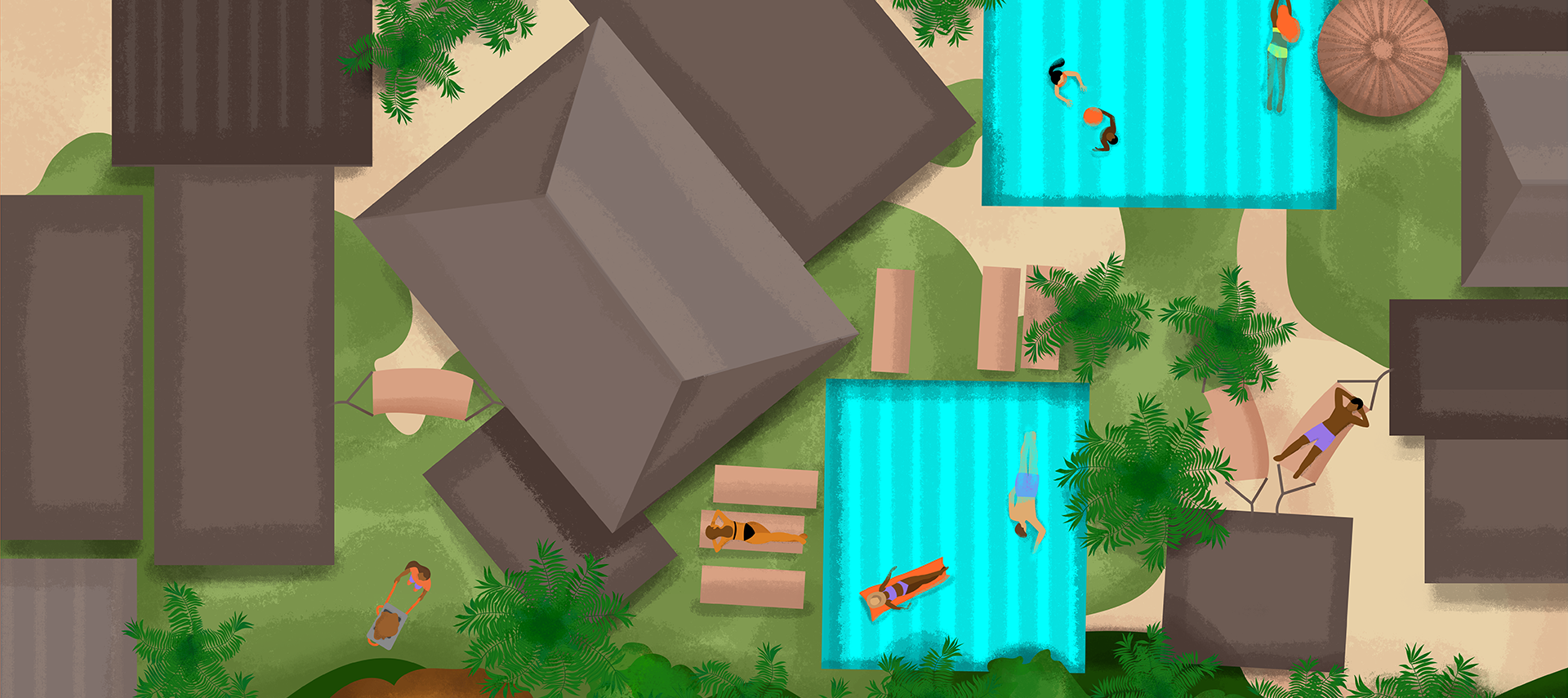

The beach paradise of the Caribbean is produced through the commodification of natural resources. Hotel owners are major financial beneficiaries. But when excessive Sargassum arrivals threaten this image of paradise and the tourism industry as a whole, those hotels are also some of the most economically impacted. To make good on the promised beach paradise and keep tourists – and their dollars – coming through the hotel doors, hotel owners need a clean beach, free of Sargassum. Many hoteliers along the Caribbean coast have significantly invested in strategies to keep the beach clean from installing barriers to hiring workers to manually rake the beaches free of seaweed. The diverse interventions have varied impact both on the amounts of piled Sargassum as well as on the larger ecosystem.

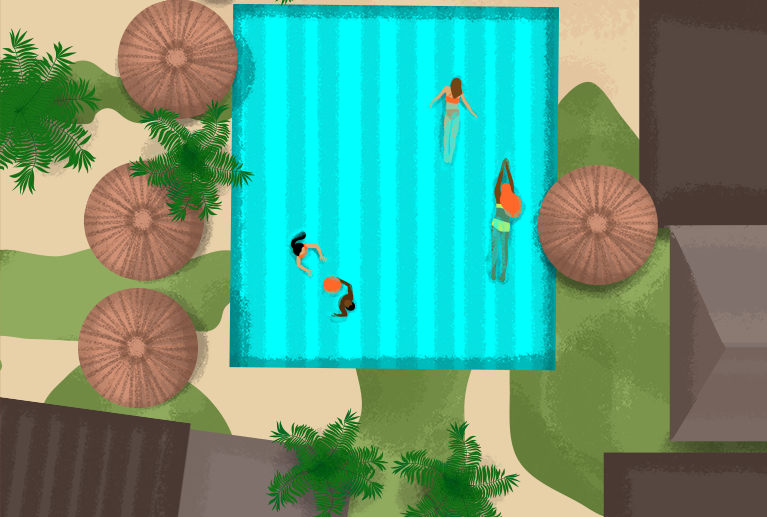

Cenotes are natural sinkholes or freshwater pools formed by the collapse of limestone bedrock, revealing underground water sources. The Yucatán Peninsula is renowned for its abundance of cenotes. These underground pools are not only geologically fascinating but also culturally and historically significant to the Maya civilization. The ancient Maya considered cenotes to be sacred places, using them for religious ceremonies and as a vital water source. Today, cenotes also play a significant role in the tourist landscape: travelers swim in the crystal-clear turquoise waters, they dive in the caves, and have drinks in the hammocks. The arrival of Sargassum impacts cenotes and their fragile ecosystem for two reasons: More and more tourists are bathing in the cenotes, leaving behind trash and sunscreen residue. Sargassum that is improperly disposed of in the jungle becomes liquid and seeps into the cenotes, leading to an increase in nutrients that alter the ecosystem.

Pause a moment to think about what makes up ‘Caribbean paradise’. You’re probably imagining white sandy beaches, palm trees offering shade and coconuts, and glistening water extending an invitation to go on a snorkeling trip. Excessive arrivals of Sargassum have made ‘paradise’ becoming less and less of a reality. Beached Sargassum piles up along the shoreline, rotting in the sun, releasing a sulfurous odor, and turning the white sand into a muddy brown. It also decomposes in shallow waters along the shore, turning the once-clear water into something that looks more like coffee; scientists refer to this condition as brown tide. Sargassum is often removed from beaches, but that also comes with its challenges: loss of sand that’s transported with the wet seaweed to its final dumping place, palm trees whose roots are exposed from the removal, and heavy machinery employed which compresses the sand and makes the beach hard enough to ride a bicycle on.